I imagine Gaudenzio lives in a 18th century house; now let me think....sorry, just fantasizing a bit

1857-68 'Un Petit Train de

Plaisir' was written by Rossini who hated trains, having had

a bad experience. This train in the piece from 'Péchés

de Vieillesse, 6. Album pour enfants dégourdis craches

soon after departure and the souls of the passengers make their

way into heaven.

For this train to be 'real' one needs to think of the 1821 Act

of Parliament that approved for a horse drawn tramway between

Stockton and Darlington. Stephenson's Locomotive No. 1 made the

trip on 27 September 1825: 40 kilometers doing between 12 and

15 kilometers an hour. In 1830 the Stephenson 'Rocket' with an

average 19 km/h and a max. 48 km/h would do the just opened Liverpool

Road, Manchester to Edge Hill, Liverpool.

No, don't want him to live in

a villa

No, don't want him to live in

a villa

Progetto ROS / Rossini Opera Stampa; a 'KAUS Urbino Project' related to the Rossini Opera Festival 2012.

A Rossini opera is essentially

a museum-piece.

&

'The Rossini opera' is a museum for farce.

Farce is a fine, old and long

continuing tradition in Italy since Plauto.

Whilst Greek 'Old Comedy', as from Menander, is direct political

(for which Menander was persecuted), the Greek 'New Comedy' as

from Aristophanes, is focused on the 'the family circle' - not

on some real 'Mr So and So', a 'me' or 'you'; rather on 'the

likes of us' - eh, that is to say, 'the likes of them', of course

- ha! ha!; 'them' always being more funny than 'us'.

To play with that is the verry heart of farce: 'free from political

and/or intellectual content'; 'Father & Son' relationships

(the powers in the family, especially when twisted in female

hands) are core business. Plautus has, on the cultural shoulders

of Menander, brought this tradition into Italy. Word-play / pun

and repetition of sounds, words / sentences that 'belong to a

personality' is a key element to built with - this becomes a

main characteristic up until indeed Rossini's opera's - dragging

(albeit sometimes splendidly) on till today ( a bare-boned example

might be 'Dinner for One', 192xs (something) by Lauri Wylie).

When in the early 1980s I was in Montefiascone (doing some research

and making a documentary on the Barbarigo project) I was lucky

to see a Plauto play in the archeological dig at Bolsena.

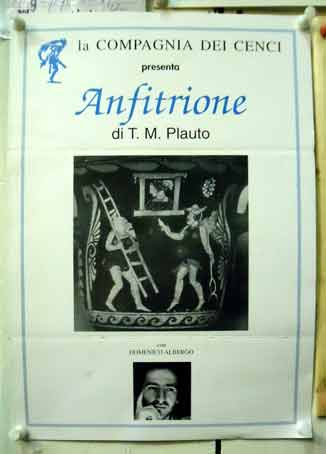

The announcement left is the

original that is still on my studio-wall.

This opened my eyes for this sort of classical theatre. I had

never seen such befor. Theatre at the time (the 1980s) in The

Netherlands was 'modern', and it had to be about 'me' and what

'I' am able to relate to. This theatre was 'Plauto' and 'his

day' (day, pretty much, as a farce has no more time to spent

than a 24 hours span) - this was look into the Classic's World

- all parallels were to be made by myself (if it needed any).

This theatre is essential word play in stories on every-day family

life: a window opening on to life as we, most of the adiences

of all time, live it.

Rossini knows well to use these characteristics in aria's, where he builds this out in the belcanto technique.

I just happened to see the older Glyndebourne production of Johan Straus' Fledermaus on tele-vision; the Guardian may not have liked it, I absolutely loved it. In fact this again was farce in the traditional sense - with the, also traditional, 'up-dating' 'improvised' jokes. The argument there was prety much on this theme of themes: do we restage with the idea of a musuem, or do 'I' (the stage-director) 'create' when working on a re-creation.

I had to think on something

else also: as I am at this moment right in the middle of a process

of making a CD with some of my own music (songs for alto and

church-organ on texts of First World War Poems), I find - this

is the very first recording of these pieces - the musicians strongly

focussed on what my essential idea is/has been.

This is far away from the sort of interpretation that is made

when 'we' stage an older work of art; somehow then this crazy

idea creeps in, where all who are involved seem to have an idea

about what they want to learn the public that is going to see

it. Most certainly, I would argue, one should learn the audience

about what the original idea was at the time these things were

fresh and we did not know the onslaught of time (on ourselves

and the actual work). A work of art could be / should be / is

like an antique ping-pong ball filled with the air of a former

time. As such it tells about how things were, like deep and hidden

older ice-fields in a gletscher can tell about the history of

the world.

Gaudenzio's house again?

Gaudenzio's house again?

Rossini sometimes wrote the

recitatives on poor paper; as a result of which the ink has bled

so badly that pieces are not to be read anymore and pieces have

been re-calligraphed by others. Such might have had an influence

on what is actually coming to us as 'original'.

This practise, in my view, does not give a free hand to us today

to cut 'there' as it is 'not original anyway', as so often has

been done.

I think it is also a very special insight to the composers mind

that 'proper aria's' are on expensive. good quality, paper, and

sometimes recitatives are not.

In a (was it 2009?) Cambridge

conference with things like "attempted to get to the roots

of the musicological discipline's construction on nineteenth-century

music <...> intellectual framework inferred from the Beethoven-Rossini

opposition < ...etc." "German critics from Adolf

Bernhard Marx to Hugo Riemann habitually identified Beethoven

with the highest values in music - and Rossini with their debasement:

lasting German profundity and universality contrasting with ephemeral

Italian banality and populism; < ... etc.".

All good and well;

and knowing my place in

an intellectual debate to be the dog's house - and ok. I would

not dare to argue (for or against) Schopenhauer (in this debate

somehow on my side I seem to remember); and on top of all that,

being biased befor even considering being a reliable voice in

the case of La Donna Del Lago (that being a Walter Scot story,

and me having a few drops of blood from 'such' places):

has anyone ever listened to La Donna del Lago?, surely if one

does, the entire argument is like dry camel-shit in an oven,

only to be used when making a proper meal.

By the way if ever there was serious ('harmonious or indeed symphonious'

if you like) music it must be the orchestra and especially the

woodwind instrument - singer dialogues in The Lady of the Lake

(by the way, Rossini was the first to see the quality of Dear

old Walter Scott).

Just a short comment on me being biased: is it possible to read Schenker and belief he is not? If you can, please, grow up!; then again one would not even want to try to learn a dog like myself about Euclid of Alexandria: I would not see the fun in being right only because one follows the rules made up by oneself beforehand.

Blame me; I'm beginning to like 'my' Rossini! Yes, there are those who dislike tulips because they are stupid flowers, and there are those who bid a fortune and cannot even find it the gutters again for these very same flowers.

On this gaudenzio-house I am of course just droodling away a bit, that being the way for me to get to grips

Rossini wrote between 1811

and 1818 some three/four opera's per year; he would scarcely

live if he did not.

He was making one third of the money of the tenor, or half of

that of the soprano at the premiere of Il Barbiere di Siviglia

- and for that having a contract to be at the three first performances

as the keyboard player, in case the orchestra of amateurs would

get lost - having no copyrights anyway as the scores belonged

to the impressario of the theater; on top of that the composer

was to be the one to stage every new opera - for that staging

was hardly a penny: "who'd value a farce". As such

Rossini did well and slowly came to 'financial security', something

we can hardly value enough - when he visited Beethoven in Vienna

Rossini was chocked to see the living conditions of this great

Austrian Maestro. Real money Rossini made in England when playing

and singing for the aristocracy (duets with the king), and better

even when he took on positions as a director at the Theatre Italien

in Paris and working for the Vienna Festival; his so called 'fortune'

never the less was made with the help of banker-friends.

no. 836 Wednesday, Aug. 4, 1824.

- " The Prince of

Saxe-Cobourg, son-in-law to the King of England, has shewn a

remarkable instance of generosity towards Rossini. The custom

with this celebrated Italian composer, is, never to go to

any musical soirees for less than 50 guineas. Ho three times

presided over Concerts for the Prince, for which his Highness

sent him 500 guineas and a diamond pin."

Now, this we conceive is nothing more nor less than a puff of Signor Rossini's, on his return to the French capital. If we could bring ourselves to believe that a Prince, who has hitherto been popular on account of his own personal conduct, as well as the endearing reeo^ection of his lamented Princess, could so far forget the liberality of the founders of his fortune, as thus to lavish on a conceited foreigner, for three nights superintendanee of a band of musicians, a sum that would keep in comfort ten British families for an entire year, we could hardly restrain the honest indignation of our feelings, from, expressing the contempt every Englishman of sense must join with us in entertaining, at such a wanton waste of British money on a worthless object.

Joseph J. Visser, Composer, Visual Artist , Author/translator & Lecturer.

The Theatrical observer and, Daily

bills of the play:

no. 928 Friday, Nov 1824.

To the Editor of The Theatrical Observer.

Mr. Editor,

I waul words to express my admiration

of the incomparable music of Weber, who I hope will go ou

in the brilliant career he has commenced ; produce many

Operas of similar high character, and lay that Italian vagabond,

Rossini, on the shelf. The conduct of that bloated maestro,

both to the Opera-riouse, ami the English public, during his

late visit, was most barefaced - he engaged to produce

two new Operas, and never wrote a line, except some trash about Lord

Byron. - Vide Maria Von Veber !

Yours, &c. TWEEDLE-DUAL

To complement the controversy:

Le Globe after the premiere of 'Guillaume Tell':

From that evening dates a new era, not only for French music but also for dramatic music in all countries.

I for myself am inclined to see truth

in this last remark; and I can see sense in a Rossini who, after

all he's done already in the rich tradition that he loved working

in, does not see fit to indeed go for the artistic struggle -

mind you, a life long struggle with an ever merciless public

- of implementing that new music.

At that moment in life, emotionally unstable and feeling/being

in fact unhealthy, he rather leaves that into the hands of his

younger collegues.

He himself never had the intention to fight an audience, or any

of his collegues - the audience, and these collegues fought him,

definitely more than would be fair on any scale.

More importantly, Rossini never did 'artistic battles'.

Historically speaking he is from the 'romantic era'; psychologically

speaking we like to think in 'romantic' terms when looking at

art.

As a public we do not know 'art' as in: the work someone does

from a very early age; we do not accept 'art as a trade' (which, in fact and whatever you rather like it to

be in the hands of the people we love to do the work that we

would not, ever, even begin to undertake, it

is; certainly for those being born before the romantic era.

Then again, after a brief pause, Rossini started on a new carreer

as a composer in the real romantic style. This part of his musical

life he himself sometimes referred to as 'sins of old age', or

simply 'sins' - this last word he had used also for publicly

failing opera's like Il Signor Burschino, a 'sin of youth' -

funny if we regard the clever playfulness he practised in that

opera. Never a revolution, but the public never the less could

not but ruin it with, ever so unfair and silly, criticisms.

I like to consider his usage of words like 'sins' referring to

his work as a fine sort of modesty that keeps his on the otherhand

excuberant life-style in perfect balance.

REVUE DE PARIS; Août, 1829 Quatrième livraison:

'De la Musique en France"

(réimpression, Slatkine Reprints, Genève, 1972):

onto this most important article, please: